On 19th February, 1942 real war came to Australia when two air raids by Japanese carrier based aircraft wrecked the town and the adjacent army and RAAF bases.

The first inkling that anybody in Australia had that something was about to occur was at 9.30am on Bathurst Island, about 80kms NE of Darwin. When the missionaries and islanders saw a huge formation of aircraft at high altitude. The mission was headed by Father John McGrath who also acted as a volunteer coastwatcher.The mission was equipped with a radio transceiver linked to the AWA Darwin Coastal Station under call sign VID. AWA ran many aeradio stations under contract to the Department of Civil Aviation with range all over Australia and as far as Portuguese Timor.

In my paper on the Adelaide Handicap I outlined the historical origins of Japan’s involvement in WW2 and I don’t propose to repeat myself on that. My principal source of reference to the events of 19th February is Douglas Lockwood’s book written as a direct record of events from his own personal experience. He and his wife were there at the time of the raid.

At 9.15 the same morning well to the south and out of sight of Bathurst Island Mission, a flight of US Army Air Corps P40 Kittyhawk fighters escorted by a B17 bomber took off from Darwin’s military airfield heading for Java. Their first destination was Koepang on Timor but after 20 minutes in the air bad weather reports at their destination prompted the controller in Darwin to call them back. The return track was well to the South and out of sight of Bathurst Island.

Back at Bathurst Island Father McGrath switched his radio to coastwatcher mode, an emergency frequency kept permanently open and monitored at VID in Darwin. He switched on his main transmitting set which took a while to warm up and at 9.35 he was ready to transmit.The Mission’s call sign was “Eight SE to VID”. He began “Big flight of planes passed over going south. Very high. Over.” At VID, the duty officer, Lou Cornock replied “Eight SE from VID. Message received. Stand by.”

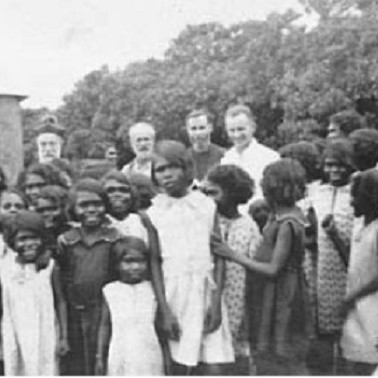

Father McGrath with the children of Bathurst Island

Father McGrath had no time to stand by. At that moment a Japanese aircraft screamed low over the mission raking it with Machine gun and cannon fire. An American Beechcraft aircraft on the ground was destroyed and Father McGrath abandoned his radio and raced to shelter.

Back at VID in Darwin, Lou Cornock stuck rigidly to the rules. He recorded Father McGrath’s message, time and readability in his log book. 0935 local time and strength 4 readability; readable but not perfect. His next message was “Phoned R.A.A.F Operations. 9.37A”. At RAAF Operations it was the job of the Duty Officer to raise the alarm by passing the message on to RAAF section of Area Combined Headquarters, next the Navy, next the Army and then the civilian air-raid wardens.

However, at RAAF Operations uncertainty reigned. Two hours earlier a group of RAAF Hudson bombers had arrived and failed to observe the established inbound “friendly” route. The Army AA gunners had a concern that the Japanese might use captured Allied aircraft in a surprise attack. The RAAF had persistently failed to observe this protocol so the Acting Gun Position Officer ordered a warning shot be fired across the path of the inbound Hudsons. This made RAAF Operations jumpy, a condition aggravated by their knowledge that the returning Kittyhawks were due causing the staff on duty to ponder if Father McGrath might have made a sighting of one of these two flights.

Consequently no alarm was set off lest it proved to be a false alarm and cause panic.

The Army maintained a series of observation posts around Darwin. Their log records “Post M4 reports six planes approaching from seawards flying at great height, unable to identify at 0938 hours”. Post M4 had trouble contacting the fixed defences but at 0950 the message reached Larrakeyah Barracks. The Navy was contacted by landline and immediately let off its own air raid siren but the RAAF was the responsible authority for raising a general alarm with a predetermined signal of four blasts 30 seconds apart. As the Navy siren did not conform to that pattern nobody took any notice.

At the Japanese end, Captain Mitsuo Fuchida who had led the attack on Pearl Harbour was now in command of a force of 188 aircraft about to attack Darwin. His formation tracked to the SE of Darwin making them hard to see against the morning sun. They kept tracking south then turned north to approach the town on a north- west heading. A telephonist based at 14th AA Section at Darwin Oval was eavesdropping on town chatter on the open party line and heard a voice saying something about a “dogfight” over the sea. This was the returning Kittyhawks on the first encounter between them and the Japanese planes. The telephonist sounded the alarm for his gunners and the Oval’s AA crews manned their guns.

Down at the wharf, No.3 gang of dock labourers had just opened the hatch of the Neptuna ready to unload its cargo of explosives and depth charges and they were knocking off for their 10.00AM smoko. When they saw these planes one of them remarked “Yank reinforcements at last”. The AA gunners at the Oval were not confused and before the siren sounded they opened fire, their shells crossing the Jap bombs in mid-air.

At that time Darwin was significantly under defended. This was due to an overall lack of resources in the entire country. There were insufficient AA guns, a hopelessly insignificant complement of modern fighter aircraft and no permanently stationed fighting ships. Prior to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour there was a lack of air raid shelters and trenches but after that there was a flurry of civilian activity constructing these. Plans were also prepared for the evacuation of civilians who were not actively involved in the war effort. At the time of the attack many of these projects were incomplete. A case of too little too late.

The AA guns were effective against horizontal high flying aircraft but were useless against dive bombers and strafing fighters. Against these the Army had Lewis guns mounted on top of oil tanks on the harbour but with only -303 calibre they were pretty useless and there were not enough of them anyway. There were many ships in the harbour that had escaped from the Japanese invasion of the Philippines and these had their own anti-aircraft defences.

The wharf at Darwin was essential to maintaining the place. Sea transport was to only means of conveying supplies of anything and the wharfies were intent of preserving their jobs for as long as possible. On 5th January, 1942, an American convoy arrived. The first vessel, the Holbrook, was going to take the wharfies three weeks to unload. The skipper decided to use his own crew and the wharfies reacted. The US base commander set up machine guns around the ship and put his men to work. A compromise was reached with the wharfies after the Minister arrived from Canberra. The convoy was then unloaded at normal speed. Other problems arose with the American units comprising a complement of black troops which offended Australia’s White Australia policy. Diplomatic niceties were exchanged but the Americans just carried on ignoring them.

The first bombs missed the wharf by 20 or 30 metres. The next stick hit it destroying one section and damaging two ships being unloaded. One bomb hit the recreation shed killing those who had just knocked off for smoko. The first explosion flicked bystanders, a locomotive and six trucks into the water and cut the oil pipeline spilling oil into the harbour which then caught fire. The burning oil drifted with the tide into the main shipping anchorage which was full of ships.

The town’s main communication centre was located near the wharf. A 250kg HE bomb made a direct hit on the post office destroying it and killing all the occupants.It destroyed the telephone exchange and cable office cutting off all civilian and most military communication.

The third wave attacked the military barracks and nearby new civilian hospital. Little or no damage was done to the barracks and the hospital did not suffer any direct hits but it was damaged by blast from near misses. The staff had been well trained to cater for patients but the sudden surprise caught many of them unable to retreat to the shelters. These people took refuge under beds and wherever they could find safety. There were some injuries but nobody was killed.

At the RAAF field located out of town, the staff could see the smoke rising and hear the thud of bombs. There were no fighter aircraft available and no AA guns. All they had was machine guns which could not reach the bombers. Bombs poured down on the hangers and workshops destroying the lot and all inside. The bombers were followed up by dive bombers and strafing fighters. Wing Commander Tindal was killed.

The raiders then turned their attack to the civilian airfield. The devastation was complete. Everything, including a Flying Doctor plane was destroyed.

The previously reported dog-fight was between the returning Kittyhawks, a Catalina and nine Zeros. The Zeros finished off the Kittyhawks and thea Catalina flying boat then turned their attention to HMAS Gunbar, an auxiliary minesweeper tasked with guarding the harbour entrance. It was armed with a single Lewis gun. The ship was not sunk but one crewman was killed.

There were many ships anchored in the harbour. Six of these were fighting ships with their own AA defences and numerous other types waiting for space at the wharf or further orders. They were nearly all caught by surprise and took a while to get up steam and underway. The prize was the destroyer USS Peary and a seaplane tender, USS William B Preston. Peary had survived four previous encounters with Jap dive bombers en route from the Philippines and arrived at Darwin on 19th February to pick up fuel. She was just under way when the dive bombers struck, severely damaging the entire ship and killing 91 crew. Peary sank stern first while still firing her forward guns.

William B Preston took refuge in the East Arm of the harbour but there she was isolated and came under very heavy attack which set her on fire and caused considerable damage. Ten crew were killed but she made it to the open sea and escaped eventually arriving in Sydney for re-fit and return to service. She was scrapped in November, 1946.

The MV Neptuna was tied up at the wharf loaded with TNT and 200 tons of mines. She was heavily attacked, set on fire culminating in a terrific explosion that killed 45 crew and totally destroyed what remained of the wharf. The Zealandia which had evacuated civilians two months earlier was sunk, the hospital ship Manunda was attacked, an oil tanker, British Motorist and a coal hulk Kelat were both sunk. HMAS Katoomba was trapped inside the floating dock but was still able to use her AA guns and was not sunk.

After the war ended Douglas Lockwood interviewed Capt. Fuchida who told him that his pilots claimed that they did not see the red crosses on the Manunda. He stated that the ship was not deliberately targeted but was so close to other ships it was impossible to avoid her. 12 crew were killed and 19 died later of wounds.

The death and destruction inflicted on the waterfront and shipping was very considerable. In all 194 were killed on ships, 19 died of wounds later and 22 wharfies were killed outright. In addition, an unknown number of personnel were lost at sea, eaten by sharks or crocodiles when the bodies drifted into the mangroves. The official total of 297 dead does not account for these unknown casualties.

The Japanese suffered a few losses of aircraft shot down by AA fire and one lucky Lewis gun shot. All in all there were five positive sightings of downed Japanese planes and an unknown number of damaged ones that did not make it back to their carriers.

The raid ended at 10.40am and the “All clear” was sounded. In 42 minutes Japan had effectively knocked Darwin out of the war.

The Second Raid

As soon as the all clear was sounded the victims emerged from their shelters and soon got into action. During the raid the waters of Darwin Harbour was filled with sailors forced to abandon their vessels and an armada of lifeboats and other smaller vessels darting around rescuing them. Burning ships in danger of exploding at any time did not deter the rescuers. The Dept. of Civil Aviation maintained a fleet of launches to ferry passengers to and from flying boats. One of these, manned by a civilian, is credited with rescuing over 100 sailors from the harbour. While her crew were still fighting fires on board, the Manunda continued to take on the injured. On the day of the raid she took on 76 patients and 190 the day after.

The Neptuna was tied up at the wharf in danger of exploding at any minute. The Barossa tied up at the opposite inner berth was hemmed in by the Navy tug Wato. Its commander displaying extraordinary courage got a line to Barossaand managed to pull her clear just before Neptuna exploded and saved the ship although it sustained severe damage.

Two contractors were loading sand onto a truck when the raid started. They raced to the wharf area to help fight fires. With bombs still falling they both dived into the water to rescue wounded wharfies and sailors from the water and others who were cut off by pools of burning oil. Their truck was used as an ambulance to get the wounded to hospital.

The much maligned wharfies who were away from the wharf rose to the occasion as soon as the All Clear sounded. They raced to the wharf to look out for mates who they knew had been working there but were turned back by a guard who was preventing anyone entering the area because of the risk of an explosion so they applied themselves to help out the military ambulances loading the injured.

The AA gunners at the oval had almost exhausted their supply of ammunition. They immediately got to work replenishing their stocks and cleaning their guns. The ammo boxes were all manhandled and there was little chatter as the gunners were deafened by the noise of the previous 42 minutes.

Fortunately there was no respite taken to feel sorry for one’s self because at 11.58an the air raid siren went off again. 54 heavy bombers from bases in Ambon and the Celebes each with a bomb load of 1,000kgs passed over Larrakeyah Barracks headed for the RAAF aerodrome. Those on the ground did not know whether to expect paratroopers or bombs. 27 approached from the south-west. 27 approached from the north-east and they converged on the RAAF base simultaneously. For 20 minutes the bombers, maintaining highly disciplined formation, circled the airfield unloading 13,000kgs of bombs on each pass smashing what remained from the first raid. The Japanese were so confident that they would not meet any resistance did not bring escorts so there was no strafing or dive bombing.

The carrier based force of Capt. Fuchida did not rest on its laurels. His dive bombers returned to attack local shipping which had made it to the open sea. Two vessels, Florence D and Don Isidro were caught north of Bathurst Island. Florence D had stopped to rescue a Catalina crew downed during the inbound dog fight earlier that morning. The ship was sunk and four crewmen were killed. They made their escape in the lifeboats and got to Bathurst Island where they remained undetected for two days after which they were given a supply drop and rescued.

One of the Japanese casualties from the first raid was Petty Officer Hajime Toyoshima whose plane crashed on Melville Island after the oil tank was hit by a -303 bullet, lost its oil and seized the engine. He was captured by a Tiwi Islander and became a POW. He was a ring leader of the uprising at the Japanese POW camp at Cowra in August 1944 and committed hari-kari that same night. His wrecked plane is on display at the Darwin Australian Aviation Heritage Centre.

After the first raid Major General David Blake made a tour of the town to survey the damage and the state of his troops. He reported that he saw no signs of panic. The Air Raid Wardens were doing their job and everyone was busily employed.

A house is destroyed after being hit by a Japanese bomb during an attack on Darwin in 1942. CREDIT:AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL

After the second raid the civilian morale turned for the worse. The general feeling was that they citizens had had enough and the only sensible course was to leave. It was at this point that the Adelaide River Handicap reached its peak. Rumours started floating that there was an order for all civilians to leave town, so they did.

There was a wide spread expectation that the Japanese would invade the next day. History now records that didn’t happen.

The RAAF base suffered the worst of any panic when hordes of airmen abandoned the base. The stations strength on 19th February was 1,104. Four days later 826 had returned. The other 278 still missing were classed as deserters

One of the principal difficulties in identifying exactly what happened on that day is the blanket of censorship brought down by the federal government. News of the raid did not filter down the eastern states for two days. Then it was mostly gossip from unofficial sources. The attitude of the government was that the news would create panic in the rest of the country and destroy morale. Compare that to the position of President Roosevelt announcing the raid on Pearl Harbour. Roosevelt took the country into his confidence and an entire nation rose in response.

Further to that, Prime Minister Curtin stated that the results of the raid were not made known so that they could not give any satisfaction to the enemy.

The other difficulties were the absence of key witnesses at the Lowe Royal Commission and the disputation of evidence from various witnesses, particularly from Abbott, the Administrator, who challenged much of the testimony against him as lies.

An example of how confused the information is the official death toll is quoted as 243. A former mayor estimates it to be 900, a worker employed to collect dead bodies and bury them claims that there were over 300 in one mass grave and Army Intelligence puts the figure at “about1,100”. On top of that many bodies were unidentifiable.

At the end of this saga Darwin was never threatened again like it was on 19th February but it was still to suffer further air raids. Darwin and other northern cities and towns were attacked by Japanese aircraft 111 times in 1942 and 1943. Darwin itself was attacked 64 times In addition, there were attacks on coastal shipping and the intrusion of midget submarines in Sydney Harbour but the raids on Darwin on 19th February, 1942 transcend the rest.

The legacy left by the raids on 19th February has lingered ever since. When most of the civilians left Darwin became a de facto military camp. Little was done to repair and restore the damaged buildings that were not vital to the war effort. Administrator Abbott moved his headquarters to Alice Springs, a move that he was roundly criticised for. As one Territorian put it, if it was OK for the King and Queen to stay in London for the duration of the war why didn’t Abbott set an example?”

After the war civilians gradually returned and restoration work commenced until Christmas Eve, 1974 when cyclone Tracey hit the town and destroyed it again.

Reconstruction started again but this time with much improved building regulations and standards. Darwin today is an attractive modern city, a Mecca for tourists in winter time and a thriving economy serving as the gateway to and from Asia.

The shock waves from the raids galvanised the government to improve the defence facilities. These have steadily been expanded and today Darwin is once again the front line of the nation’s northern defences. It is home for permanent and substantial defence projects from all of the services the major one being the Tindal Air Base named after Wing Commander Arthur Tindall who was killed in the first raid.

In addition it is also home to a rotating programme of the US Marine Corps and the repository of much of the Singapore Air Force.

"Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall."

- Confuscious.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS