'Music and women I cannot but give way to, whatever my business is.' That's what Englishman, Samuel Pepys, (definitely a man after my own heart) wrote in his diary during the 1660s.

Whenever I see engravings or paintings of those lavish, seventeenth century dining scenes, I wish I could be there, transported back through the annals of time. I'd like to be one of the guests for the evening, join the conversation, taste the food, enjoy the wine and hear the music. But, only for the evening.

Everything was different in those days; living standards, transportation, manners and particularly, the food. We learn this from reading journals of the time and those of Samuel Pepys describe the era quite well, particularly as he was such an articulate and literate character.

Pepys's London journals, written in shorthand over the course of ten years, is a more exciting reading than most novels.

Pepys takes the reader through his daily routines, to work at the Admiralty, through food shops, on carriage rides with his ladies, and to his many fine and memorable dinners.

London's population at that time was about 400,000 and owing to a succession of crop failures and economic strife, the peasants lived mostly on bread, cheese and beer. Sounds okay to me. The gentry, however, stuffed themselves with large quantities of meat that were readily available at most taverns or cook shops for those with the means to indulgence.

The French traveler, Henri Mission wrote:

'Generally, four spits, one over another, carry round each five or six pieces of butcher's meat, beef, mutton, veal, pork and lamb; you have what quantity you please cut off, fat, lean, much or little done; with this, a little salt and mustard upon the side of a plate, a bottle of beer and a roll; and there is your whole feast.'

Such a dinner would have cost the eater a labourer’s day wage at the time. And, so it seemed, there was no shortage of customers. The English cared little for vegetables and salads and even less for fruits. Some churches and wealthy estates grew an impressive array of peaches, plums, and apricots, but they were enjoyed by a select few. It seems they were almost kept as a secret. Pepys largely avoided salads, vegetables and fruits, not because of cost, but because they gave him nasty gas attacks.

His frequent outbursts of flatulence became a sniggering source of entertainment for hotel and Inn servants as poor Samuel would excuse himself from the table and sneak off to an unused room to reduce pressure in lively musical form.

Samuel was particularly fond of his wife's preparation of buttered anchovies and eggs (no wonder he had gas problems). Although it sounds more of a breakfast dish, he insisted she make it for dinner parties. You decide which, although it goes rather well for a Sunday brunch served with an icy-cold glass of Chardonnay. Serves 6.

BUTTERED EGGS WITH ANCHOVIES

6 anchovy fillets

3 tbs. white wine

12 eggs

50 gr. pistachio nuts finely chopped

1 tbs. butter

6 slices whole wheat bread

Mash the anchovies in the white wine. In a bowl, lightly whip the eggs, add anchovy mixture and nuts. Melt the butter in a pan, add the eggs, cook gently stirring to make scrambled eggs. Serve on whole wheat toast with freshly ground pepper.

Now you know what the wealthy ate in Britain several hundred years ago.

Footnote from Monty:

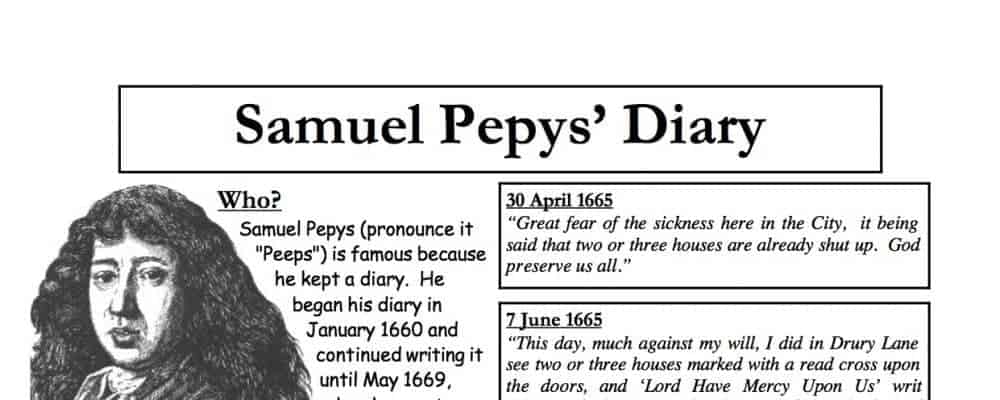

Samuel Pepys, a name that may not immediately ring a bell for many, was a remarkable figure from the 17th century whose writings have left an indelible mark on history. He is best known for his captivating and candid diaries, which provide a unique window into the tumultuous times of the English Restoration period.

Born on February 23, 1633, in London, Samuel Pepys came from modest beginnings. He grew up during a period of significant political and social upheaval, including the English Civil War and the Commonwealth era. Despite these challenging times, Pepys managed to secure a position as a clerk in the Exchequer and later in the Navy Office.

Pepys began his diary on January 1, 1660, and continued to write faithfully for almost a decade, ceasing only when concerns about his deteriorating eyesight led him to give up his daily entries. These diaries, written in a shorthand code, document his personal life, professional career, and the events of the time. They offer unparalleled insights into daily life, politics, fashion, social mores, and notable events, including the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the plague outbreak of 1665.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS