There are men who live great adventures and there are men who write about them. Ion Idriess did both. With a swag on his back, a rifle in hand, and a notebook never far from reach, he wandered the sunburnt edges of Australia, from the opal fields of Lightning Ridge to the crocodile-haunted waters of the north.

And then, like a bushfire racing the wind, he lit up the imagination of a young nation still finding its story.

Born in 1889 in the sprawl of an emerging Sydney, Idriess was never meant for city living. His spirit roamed from the start - drawn to the scent of eucalyptus and the promise of gold hidden in the hard, unforgiving dirt.

He left school early, drifted through tin camps, fencing runs, and camel tracks, learning the language of the land the hard way, with blistered feet and sun-seared skin.

In the bloodied hills of Anzac Cove, Idriess served with the 5th Light Horse Regiment as a spotter for a quiet, deadly marksman named Billy Sing as we discovered a few days ago. Sing was a half-Chinese Queenslander with the uncanny calm of a lizard on a hot rock and the eyes of a hawk. Together, the two formed a fearsome pair....Sing behind the rifle, Idriess with the binoculars, eyes scanning the enemy trenches, breath held, heart pounding.

Idriess never forgot those days. He would later call Billy Sing “the Assassin of Gallipoli,” not in mockery but in solemn reverence. He saw the courage, the cost, and the sheer endurance of those young Australians fighting a war that too often felt forgotten. His diaries from the war would become The Desert Column (1932) - a raw, powerful book written in the plain, honest language of the digger. No purple prose. No politics. Just the truth as he lived it.

After the war, with shrapnel in his body and stories in his soul, Idriess turned full-time to writing. And oh, how he wrote. Books flowed from his pen like water from a Queensland billabong....over 50 of them by the end.

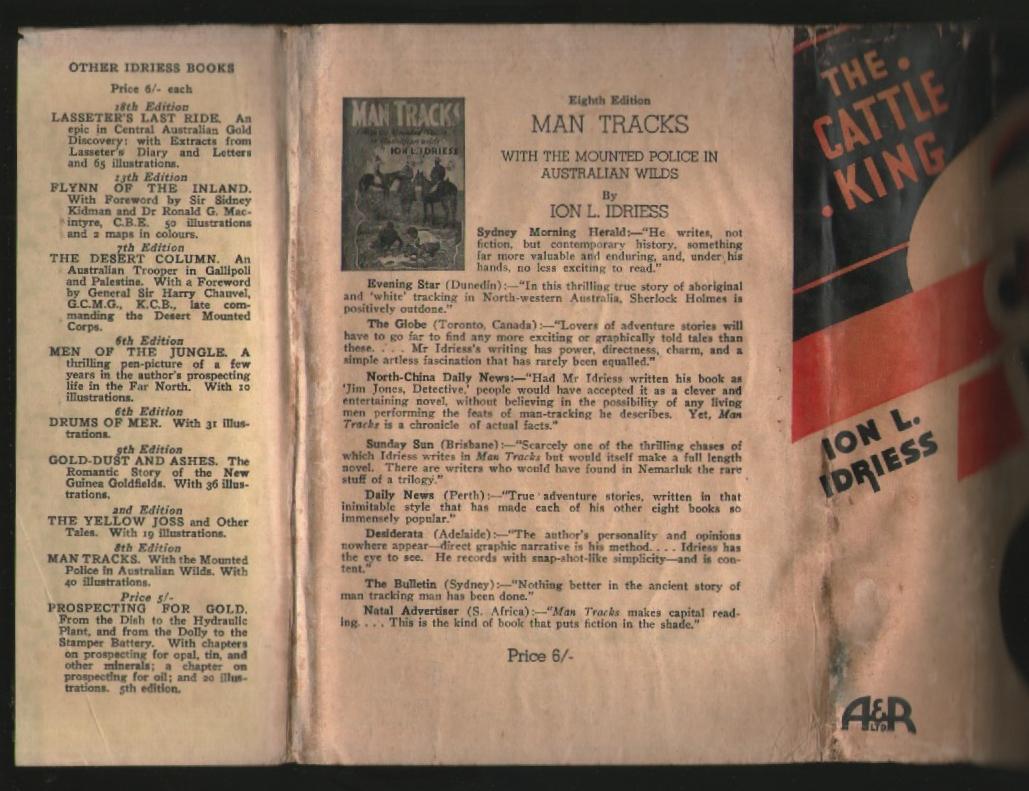

Lasseter’s Last Ride told of a doomed gold expedition and the unforgiving cruelty of the inland. The Cattle King captured the life of Sir Sidney Kidman, a man who owned more land than some countries. Flynn of the Inland celebrated the dreamer who brought medicine to the most remote corners of the continent.

But Idriess was more than a recorder of fact; he was a weaver of wonder. His tales weren’t just about hardship; they were about hope, determination, and the quiet greatness of ordinary people. He gave voice to Aboriginal warriors, Afghan cameleers, Torres Strait Islanders, and dusty bushmen who might otherwise have been lost to time. He understood that the soul of Australia wasn’t found in parliament or polished cities, but in the red dirt, the cattle tracks, the corrugated-iron pubs, and the silent resolve of those who made a life in the middle of nowhere.

To read Idriess is to sit down with an old mate by the campfire. You can almost smell the billy tea and hear the dingoes howling in the distance. His prose doesn’t shout; it leans in close and tells you something worth remembering. And behind every yarn, there’s a twinkle of admiration - for the country, for the characters, for the struggle.

Even in his final years, long after the goldfields had gone quiet and the Light Horse had become legend, Idriess remained a humble observer of his people. He didn’t seek accolades. He didn’t ask for monuments. He’d already built his own...in ink and paper.

Ion Idriess died in 1979, aged 90. The world had changed....cities had grown, outback towns had vanished, and the larrikin spirit was fading under the weight of progress. But his books remained, like ghost gums on an empty plain....still standing, still speaking.

In a country often unsure of how to honour its own, Idriess quietly built a library of national identity. He helped us remember what it meant to be tough but kind, brave but unpretentious. His writing still stirs the heart, because at its core is something we long for - connection. To the land. To the past. To each other.

Idriess wasn’t just a chronicler of the past - he was a fierce advocate for shaping Australia's future. One of his great passions was the Bradfield Scheme, a bold vision to redirect coastal rivers inland to irrigate the arid heart of the continent. He saw it not as a pipe dream, but as a national duty....a way to make the centre bloom, to support settlement, agriculture, and prosperity beyond the coastal fringe.

He wrote and spoke often about the potential of the inland, believing that Australia had turned its back on its greatest untapped resource. In Idriess’s mind, water was life, and the desert could be transformed. He argued that daring, ingenuity, and nation-building vision were not relics of the past, but vital tools for Australia's survival.

Suggested Reading List

-

The Desert Column (1932) – A soldier’s unvarnished diary from Gallipoli and the Middle East, which was based on the diary he kept during the war and is still considered one of the finest soldier’s accounts of Gallipoli and the Sinai-Palestine campaign.

-

Lasseter’s Last Ride (1931) – A thrilling tale of obsession, gold, and the brutal centre.

-

The Cattle King (1936) – The sweeping biography of Sir Sidney Kidman.

-

Flynn of the Inland (1932) – The story of John Flynn and the Flying Doctor Service. ( something I really want to get stuck into at some stage. )

-

Nemarluk: King of the Wilds (1941) – A gripping account of resistance and survival in Arnhem Land. ( Much better than Dark Emu ..... )

-

Drums of Mer (1933) – Deeply evocative writing about the Torres Strait Islands.

So here’s to Ion Idriess - soldier, storyteller, bushman, and the keeper of Australia’s wild, wandering soul.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS