As the Xmas/New Year break approaches many people will have their eyes on the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race; a traditional event starting on Boxing Day.

One of the several unticked items on my bucket list is to sail in the Sydney to Hobart. Back in the 1970’s and early 80’s I crewed on an ocean racer out of Sandringham Yacht Club in Melbourne. The boat I was on was a Carter 30, an English design that could better be described as a Slow Boat to China rather than a racing thoroughbred.

Nevertheless we competed each Saturday in races on Port Philip Bay and, when organised in various races “Outside” in Bass Strait. Our pinnacle was in 1984 when we came 3rd on handicap in the Melbourne to Devonport.

The ambition of most of us was to sail in the Sydney/Hobart but the demands on time and money prevented it.

The Sydney to Hobart started accidentally in 1945 when a Royal Navy officer stationed in Sydney, named John Illingworth had a speaking engagement at the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia. He happened to meet Peter Luke, one of the club’s founders, that he and a friend were going to cruise down to Tasmania and suggested that Luke might like to come too. Luke liked the idea and Illingworth said “Why don’t we make a race of it?”

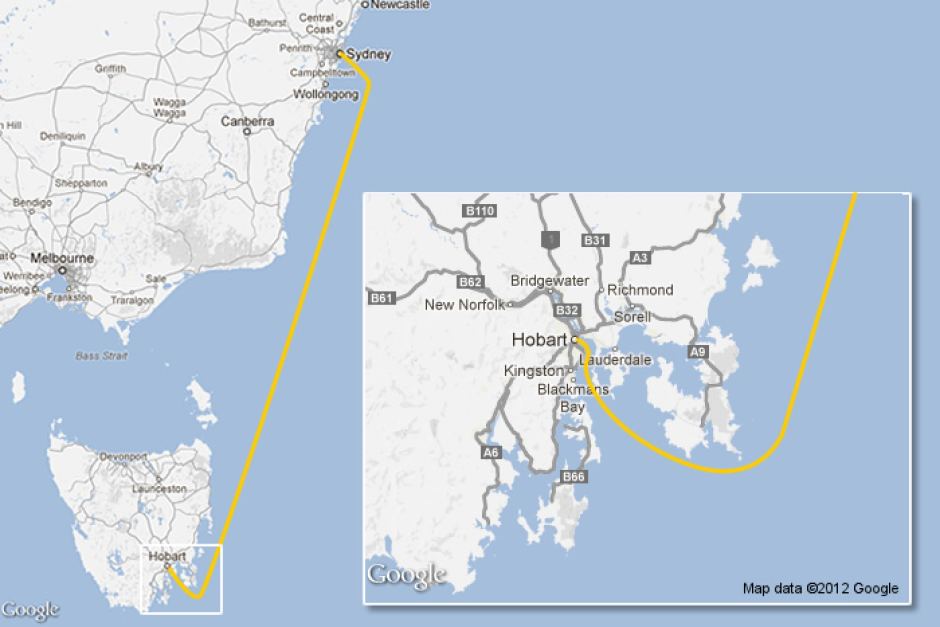

The idea spread quickly among the members and 9 boats in all decided to join in. The Royal Yacht Club of Tasmania was contacted and agreed to look after that end. Thus on Boxing Day, 1945 the 9 yachts set sail for Hobart, a 628 nautical mile trip as the crow flies although there aren’t too many crows to be seen out there.

Navigator Bill Lieberman on Wayfarer in the 1945 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

The yachts concerned with the exception of Illingworth’s, were heavy displacement boats intended for cruising, not racing. The crews also were a bunch of enthusiastic amateurs rather than dedicated racing yachtsmen like those who dominate the race today. Two days into the race a south westerly gale struck the fleet. One 52 footer hove to for 38 hours before putting in to Jervis Bay and retiring. The yacht was unharmed but the crew were violently ill. Another ran for shelter behind Montagu Island and waited for the storm to pass. Another remained hove to for 24 hours before proceeding. Public concern caused the RAAF to despatch a Liberator bomber to spot the fleet. Two of them were not sighted until the 5th day when they were near the Tasmanian coast. Illingworth’s boat was first into Hobart and Luke’s was the last, arriving in the afternoon of January 6th.

The crew of Wayfarer in the 1945 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race: (Left to right) Geoff Ruggles, Len Willsford, Brigadier A.G. Mills, Peter Luke (at rear), Bill Lieberman, Fred Harris. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

Notwithstanding the terrors of the first race, the following year there were twice as many starters, including 6 from Tasmania. Interstate and overseas boats suffer a huge handicap in that they have to sail to Sydney to be at the start line. This places prohibitive demands on time for many aspiring yachtsmen to say nothing of the costs. Still, many do so and have done since that second race.

For several years the starters numbered about 20. In 1956 it jumped to 28 but three gales during the race that year put some fear among the aspirants and the next year it dropped back to 20 where it remained for several years.

In the early 1960’s, the Halvorsen Brothers dominated the race, winning 3 years in succession. The Halvorsens took a leading role in the development of Gretel, Alan Bond’s yacht that won the Americas Cup in 1967. The Sydney to Hobart had stimulated interest in yacht racing in general and ocean racing in particular. This period saw the development of yacht design and construction dedicated exclusively to ocean racing. Ocean racing is a rich man’s sport. The cost of constructing and racing these dedicated boats is beyond the capacity of all but the most wealthy and the most enthusiastic. It has become a professional sport with the emergence of the maxis, the huge sleek yachts that sail from one regatta to another manned by full time professional crews which sail in a class of their own.

The crew of Ilina during the 1960s, with a young Rupert Murdoch third from the left leaning on the boom. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

Still, there are opportunities created for more impecunious crew members who come through the ranks of smaller Olympic class yachts and by their seamanship skills earn a place aboard the bigger boats.

In 1998 the race suffered its worst disaster. As the fleet was approaching Bass Strait a massive storm hit with gigantic waves and very high winds. 7 boats were abandoned at sea and lost. 6 sailors were drowned with a further 70 sustaining severe injury. 30 civil and military aircraft took part in rescue missions to save 55 sailors from 12 badly damaged yachts. Of the 115 boats that set sail from Sydney only 44 reached Hobart.

This race may have been the worst but it was not the first where lives have been lost. In 1984 a very severe storm struck the fleet and many retired. One of these was Yahoo II. She had retired and was making for shelter when one of the crew, an elderly experienced yachtsman, was swept overboard as he was retiring from the deck to below. He had momentarily undone his lifeline and went at that critical moment.

70 boats retired from the 1984 race due to the severity of the storm.

Start of the 1986 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Archives

The expression “hove to” refers to a boat at a standstill with head to wind to ride out severe weather or fog. It is a difficult manoeuvre for a yacht under sail in heavy weather but undertaken as a safety measure.

In the 1989 race a crew member of Flying Colours was killed when the mast snapped and he was hit by flying rigging at 2.30am 60kms south east of Gabo Island. A doctor was lowered from a helicopter but could not revive him. Extra fuel was also lowered onto the yacht so that it could make its way to Eden.

The cost of the losses and rescue missions of the 1998 race has been estimated at $30 million. The NSW coroner criticised the Cruising Yacht Club for inadequate preparations. In my strong opinion this is grossly unfair and a display of ignorance. At the start of every race it is emphasised by the sponsoring club that it is the responsibility of EVERY skipper to decide if he is going to start or not given what weather or other conditions might be predicted or expected. Ocean racing is a dangerous and serious business and the race rules do not allow enthusiastic amateurs to join in on a whim by simply paying the entry fee. Competing boats must comply with extensive safety rules, crews must attend pre-race briefing sessions, the club provides a mother ship for the whole duration of the race and every boat must report in by radio according to a set schedule to ensure that all is well on the entire fleet.

The 1998 disaster exposed flaws in many facets of the race and yacht construction but the club had done everything conceivably possible to protect against all then known hazards. The 1998 storm was unprecedented. One of the casualties was an 80 footer called Winston Churchill, a beautiful heavily built cruising boat formerly owned by Sir Arthur Warner, a prominent Victorian politician. I had the pleasure of sailing on her in 1957. She was a boat that you would sail on anywhere any time in any weather without a second thought but she had been bought by a syndicate who decided to convert her into a thoroughbred racing boat that she was never designed to be. If her original design and construction had been retained I am certain she would still be sailing today. It is easy for pontifical adjudicators to be wise after the event and to that extent I come back to the basic rule that it is the skipper’s responsibility to decide to start or not, or even in this case to retire. Many yachts decided to retire and found haven at Eden on the NSW south coast.

The rules for personal behaviour on board any yacht is in the hands of the skipper. On the boat I sailed in there was a rule that once “outside”, meaning outside Port Philip Heads, lifelines had to be worn and attached at all times. My own rule was that I had two lifelines attached to my harness. In that way when I was changing position I was always attached to the boat as I changed the position one line at a time. If a man goes overboard from a sailing yacht it is going to be 99% fatal for two reasons. First because of the underlying swell of the ocean the man overboard will be lost from sight very quickly. Second, a yacht under sail cannot just turn about onto a reverse course to pick him up. A yacht under sail running down wind or reaching in a cross wind must tac back in a series of zig zags to reach the spot where the man went over. Depending on the sea and wind conditions this may take a long time during which the man overboard will have drifted well away. Wearing life jackets to do normal routine crew work is impractical. The best defence is to be hooked on with a lifeline at all times when above deck, even in calm weather.

My brother was living in Adelaide many years ago and crewed on a yacht there. On a trip home from Kangaroo Island a man was lost overboard. It was late in the day and the sun low in the sky. The crew on deck tried to keep him in sight but lost him in the fading light and he was never seen again.

Familiarity breeds contempt so it is said but on the ocean this rule cannot be discarded. One slip and you are gone. It only takes one.

The Sydney to Hobart has attained international acclaim as the only race to be held in the southern oceans and challenge the Roaring 40’s. The race itself is now part of the international racing circuit known as The Southern Cross Series. Sponsored by the CTCA out of Sydney it is open to teams from around the world. It is not held every year but when it is the Sydney to Hobart is the final race in the series.

One of the unluckiest finishes occurred in 1983 when two boats, Condor and Nirvana were running neck and neck for the finish. Condor, an American boat,decided to pass Nirvana to windward by going closer to the shore and in doing so ran aground just 5 miles from the finish. She was stuck on the rocks for 7 minutes and it was all over Red Rover.

It does not necessarily follow that the biggest boats are the winners. Certainly line honours go to one of the maxis but the race itself is a handicap race and it is rare that one of the maxis is declared the outright winner.

The smallest boat to start in the race was a 1932 built boat Maluka of Kermandie. She was 9.01 metres long and sailed in her first Sydney/Hobart in 2006 finishing 8th overall.

The 2023 race starts at 1.00pm on 26th December. It is a year of the Southern Cross Cup and is likely to attract a large fleet as a result with boats from a number of overseas countries competing. The race is again sponsored by the ROLEX watch company but still organised by the CYC and the Royal Yacht Club of Tasmania.

Right now there are 132 entries for the 2023 race with starters from all states plus overseas yachts from New Zealand, USA, Germany, UK, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Cayman Islands and New Caledonia.

Naturally there is a lot of festivity surrounding the race both at the Sydney end at the start and the Hobart end at the finish. Yachtsmen are unfairly painted as a boozy lot by those who don’t know. The rule on our boat was no alcohol when underway on the ocean or the bay. Once in port there were no rules. One of the good parts of the Melbourne to Devonport race was that Boags Brewery handed each yacht a carton of beer as it crossed the finish line. I don’t know what happens in Hobart but suspect it might be champagne.

They deserve it.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS