Each war seems to produce its own under-appreciated heroes who, for reasons that have nothing to do with their courage, competence or devotion to duty, are by-passed for promotion or otherwise demoted.

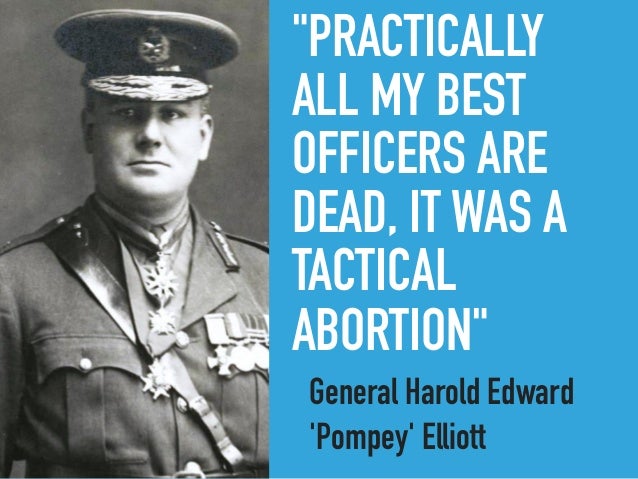

In the Boer War it was Breaker Morant, in WW2 it was Brig Arnold Potts and in more recent days Cpl Ben Roberts-Smith. In WW1 it was Brigadier General Elliott, otherwise known as “Pompey”. Elliott was one of the most direct and forceful brigade commanders in the Australian Army.

Loved and admired by the troops he commanded because they knew that he would never ask them to perform tasks that he was not willing and able to carry out himself. He was an outspoken critic of the British Army higher command and of the Australian as well when they deserved it. His belligerence and refusal to kow-tow to British higher authority was the seed of his undoing. He clashed with Kitchener, Haig and Birdwood and the fact that he was usually proved right, probably carried more weight against him that his insubordination.

Pompey Elliott was born in an era when Australia seemed to have an endless supply of natural leaders, adventurous explorers and trail blazers, innovative business people and an inborn ethic that gave precedence to common sense.

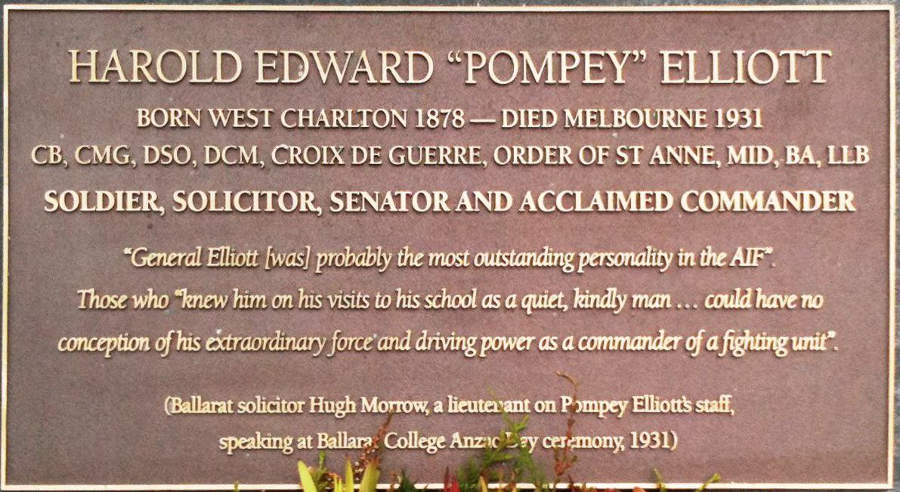

H.E.Elliott was born at Charlton in Victoria in 1878. He was studying law at Melbourne University when he interrupted his studies to enlist in the 4th Victorian (Imperial) Contingent to serve in South Africa in 1900-1902. He served with distinction and was awarded the DCM. He was mentioned in despatches 7 times and was commissioned in the 2nd Royal Berkshire Regiment but remained attached to his Australian formation. He was specifically congratulated by Lord Kitchener for his service with the Border Scouts. He was committed to serve his King and country.

In 1903 he returned to his legal studies qualifying as a LLM and BA in 1920 after establishing his own law firm, H. E. Elliott & Co in 1907.

In 1904 he re-joined the Army as a 2nd. Lieutenant in the 5th Infantry Regiment (militia). In 1913 he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in command of the 58th Battalion. At this stage his whole heart and soul were devoted to the Army.

When the AIF was raised in August 1914, he was appointed to command the 7th Battalion of the 2nd Brigade. In his university days, Elliott was a good footballer and a champion shot putter.

He was a big man physically and this, together with his boundless energy, strength of character, and explosive temper quickly made him one of the more prominent members of the AIF. It was here that he was given the nick-name “Pompey”. He did not like the name but it stuck with him. Hard training and stern discipline were the foundation of his reputation and the high degree of efficiency of the 7th Battalion.

On 25th April, Elliott was in the fifth boat to approach the beach and engaged in his usual position of leading from the front. He was wounded, shot in the foot. He was evacuated and returned to his unit in early June.

Pompey supervising his battalion’s departure from Alexandria on his horse Darkie.

The first of his major encounters was on 8th August at Lone Pine when his unit relieved part of the 1st Brigade and held the position against Turkish counter attacks for the next 24 hours. Seven Victoria Crosses were awarded for this action, four of them being from Elliott’s battalion yet his contribution was not noted. He was told by the divisional commander, General Walker, that his name had been at the top of the list of recommendations but he did not receive any. This was the first of many resentments he forged and by war’s end it had become an obsession.

In August he was again evacuated due to illness and did not return to active duty until November when he was again evacuated with a sprained ankle. He returned to duty in February, 1916, by which time the ANZAC brigades had moved to the Western front in France where he fought in most of the great battles and he was promoted to command the 1st Brigade. On 1st March he was promoted again to Brigadier General and appointed commander of the 15th Brigade as part of the newly created 5th Division. He trained this brigade the same as he had trained his battalion and it became the leading brigade of the division.

Its first major engagement was the Battle of Fromelles. Elliott could see the hopelessness of the task given to the Australians but they were ordered to attack anyway by the British High Command despite the protestations of Elliott as to the hopelessness emphasised by the first two battalions suffering major losses of 1,452 killed in the first 24 hours; the worst result ever suffered by any Australian unit before or since. Elliott’s assessment of the position was based on his own personal reconnaissance, an attribute that no other commander of his seniority could claim. Elliott was at the front line with his troops when the order to withdraw was given.

C.W.E Bean’s assistant records Elliott greeting the returning survivors with tears streaming down his face and shaking hands with each and every survivor.

Although Elliott was personally very brave and willing to take undue risks he never asked his troops to do things that he did not believe that they were capable of doing yet they carried out some brilliant actions that staggered other units and commands.

In a letter to his wife after the successful capture of the German position at Polygon Wood he wrote:-

“It is all due to the boys and the officers like Norman Marshall … It is wonderful the loyalty and bravery that is shown, their absolute confidence in me is touching—I can order them to take on the most hopeless looking jobs and they throw their hearts and souls not to speak of their lives and bodies into the job without thought. You must pray more than ever that I shall be worthy of this trust, Katie, and have wisdom and courage given me worthy of my job”.

It is said that Elliott could do things with Australian troops that no other commander could do. A large part of the secret of his success was his selection of officers. His first clash with Birdwood and Brudenell White was in March, 1916 over the appointment of his battalion commanders. Elliott was given some officers who were, in his opinion, unsuitable. He was told that they must remain and that their reputations were sacred. He replied that the lives of his men were more sacred.

This was the first of many anecdotes surrounding his objections to decisions of higher command. In addition he frequently wrote reports criticising senior commanders and the performance of troops on his flanks. After his success at Polygon Wood he wrote a report regarded by Birdwood as so outrageous and inaccurate that he ordered that all copies of it be destroyed. The report was highly critical of a neighbouring British division.

After Polygon Wood he was confident that when the next vacancy of divisional command arose he would be appointed. After his stunning defeat of the German Army together with Lt.Col William Glasgow’s 13th Brigade, at Villers Bretonneux, he was even more confident of promotion but it was not to be. Gellibrand and Glasgow were promoted to Major General and given divisional commands. This was a shattering blow to Elliott who wrote a very strong letter of complaint to Brudenell White who was unmoved to the point that he invited Elliott to withdraw the letter so that is would never reach Birdwood. It was not withdrawn.

His victory at Villers Bretonneux has been described by the commander of the British 23rd Brigade as follows:-

“Perhaps the greatest individual feat of the war – the successful counter-attack by night across unknown and difficult ground, at a few hours’ notice, by the Australian soldier”

Brigadier-General George Grogan, 23rd British Brigade

Two incidents are thought to have been instrumental to his rejection.

First was under his orders, a British staff officer was arrested for looting wine at Corbie. Elliott had it made known that looters would be publicly hanged. The guilty officer complained to General Headquarters. Second was a written instruction to British officers who were rounding up stragglers that any who hesitated were to be shot. The order was cancelled by General Hobbs.

For the rest of the war he nursed his grievances but did not allow them to change his style of leadership. In August, 1918 he was wounded again but remained on duty. His final parade of his troops occurred in January, 1919 when all of his battalions paraded voluntarily and marched around his headquarters cheering him. Since 1915 he had served his country with outstanding distinction and had been rewarded by appointment as CB and CMG, awarded the DSO, mentioned in despatched 7 times, was awarded the Russian Special Order of St.Anne, the French Croix de Guerre and a Special Order of the Day by the commander of the French 31st. Corps.

By the end of the war, Brigadier General Elliott had fought at Gallipoli, Fromelles, Ypres, Amiens, Villers-Bretonneux and Peronne on the Somme. Picture: Australian War Memorial

On the day of his arrival back in Melbourne in June, 1919 he was summarily dismissed from the AIF. He returned to civilian life to rebuild his failed law practice. In September he rejoined the militia as commander of the 15th Brigade. He stood for parliament and was elected to the senate in 1919 and 1925 and continued to harass the military seeking redress for his grievances but all of these were unfruitful and rejected at every stage.

Even after the war ended he did not give up his desire to enrich the lives of the men who served under him. He became heavily involved in the affairs of the RSL and was chiefly responsible for redrafting its constitution.

He continued to conduct an active and forceful public life. In 1923, joining with Sir John Monash, he urged his former troops to enrol as special constables during the police strike. He was ever critical of the British cabinet for the failure at Gallipoli published in the Adelaide Press.

In 1927 he was promoted to major general in command of the 3rd Division but in his eyes this was too late.

The sense of frustration and the rigours of his war service undermined his health. Early in 1931 he was admitted to hospital suffering from high blood pressure. When discharged he did not return to the senate. On 23rd March he was found with a self-inflicted wound to his arm and was rushed to hospital where he died. An inquest returned a verdict of suicide and he was buried with full military honours at Burwood cemetery in Melbourne. His portrait hangs in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

There were no monuments erected honouring Elliott’s contribution to our military history until 2015 (as there had been for others like Monash and Birdwood.)

On hearing of his death, Charles Bean wrote the following:-

So Pompey Elliott is gone! … The old soldier has laid down his arms … we can picture Pompey going round the turns of that long road that we all must travel some day, with his head held high, his senses alert, his strong chin set. It is not the first time that he has gone out alone into no man’s land. We know this about Pompey; he goes out as a soldier, utterly unafraid … History will do him an injustice if it does not hand him down to posterity as – with very few peers – one of the outstanding and most lovable characters of the AIF.

Calder Highway (High Street), Elliott Gardens, Charlton, 3525. Dedicated Sunday 24th May, 2015

LEST WE FORGET.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS